I had been on my way to San Juan, when I found myself in that cute town of Chumbicha where I ended up staying a couple of days. Finally, when it was time to get back on the road to San Juan, I realized that I was really close to the National Park Talampaya and the Provincial Park Ischigualasto. (It took me a week of stumbling over that name before I was able to pronounce it.)

A French friend that I had met in Salta had recommended those parks to me, but it seemed that getting there and enjoying them without a car was quite a challenge. Was I up for the adventure of finding my way there? Or should I just head straight to San Juan? I figured I could ask for more information in the next major city (La Rioja) and make a decision based on what I learned.

I fortuitously caught a ride to La Rioja with two women from Chumbicha – a medical student and her mom. The mom was dropping her off in La Rioja where classes were starting back up for the semester. We filled the entire 1-hour ride with great conversation so that it felt like it ended too soon.

We joked about many cultural differences between the US and Latin America and between big cities and small towns, including the tendency to fire off personal questions to a stranger. She inquired if it had made me uncomfortable when she asked me all those personal questions, and I realized that I hadn’t even noticed.

I had to think back to realize that she had in fact asked me all the personal questions that might be considered intrusive and offensive to someone from the US culture but are typical of conversations among strangers in Latin America – “Are you married? Do you have kids? How old are you? Have you dated someone from here?…”

I guess I’ve gotten used to it, having lived in a small town in Latin America for 3 years. (I wonder if I have started asking people I recently met very personal questions, without realizing it…)

She reaffirmed what I had sensed about the town of Chumbicha. It’s quiet, there are some problems, but there was no real crime, everyone knows everyone, and everyone comes together to help each other out when there is a problem. Like any small community, everyone talks about anything and everything, so while it can be tricky to maintain a private life, she sets boundaries on what she shares with people. And she felt that people really accepted diversity within the community, in terms of lifestyle, religion, and sexual orientation.

As I walked into the bus station in La Rioja, I reflected on all the incredibly friendly people I had met and that little gem of a place I had found just because I had gotten off the bus at a random stop along the way.

So that’s why, about six hours later, I didn’t even think twice about getting off the bus in a small town that appeared on the map close to the parks where I was headed. I had never heard of it before. It wasn’t even mentioned in all the internet research I had done about getting to the parks. But it was located just 20 minutes from the national park, and the bus driver confirmed that there were places to stay there.

So as I gathered my things I went looking for a place to stay. I navigated away from the signs boasting rooms with personal bathroom and a swimming pool, and found a hand-painted sign “hospedaje” outside a tiny convenient store protruding out of a house. I called out and at first no one responded, but I hung around a minute – I’m not sure why, I guess I just had a good feeling about this place. After a minute, a young woman my age came out and told me the owner had just left to sign her kids up for school and was on her way back.

As I waited about 15 minutes for the owner to come back, I thought about how good I have gotten at this patience thing. Normally I would have been seriously bothered by having to wait more than a minute and I might have moved on. But I had no problem waiting, despite the fact that I was hot from the strong sun and hungry from traveling all day.

Some parrots (“loros”) flew overhead, and I took off my backpacks and stood in the shade of a tree. Suddenly something hit me on the shoulder. I looked around and realized that the fig tree I was standing under had just offered me some of its fruit. What great hospitality! As if it had known that I was hot and hungry!

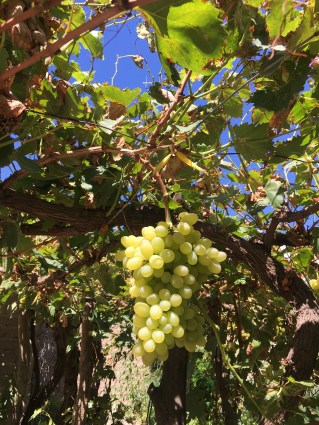

Turns out that the humans were in fact just as kind and hospitable as the tree. After letting me get settled in a private room with its own bathroom and wi-fi, they invited me to share some mate (pronounced “mah-tay”) and some grapes (and raisins) fresh from their grape vine.

OK, I’ve mentioned mate in other posts, but I haven’t explained it yet. Mate is an essential part of Argentine culture. If you know an Argentine, you should know about mate because 99.99% of Argentines drink mate. (I made that statistic up.)

Mate is not just tea. It is a ritual.

Mate is an herb from northeast Argentina (and Paraguy and southern Brazil).

Mate is also the name for the round little insulated cup that you drink mate from (usually made of wood, a gourd “calabaza”, or metal).

It is drunk from a metal straw (“bombilla”) that is placed in the mate in a special way, with the mate tea poured on top. The hot water is poured into the same spot every time so that it forms a small little indention in the tea, but only in one spot, not disturbing the rest of the mate. When you drink mate, you finish all the water in the cup before refilling it. (I have had to learn all this mate etiquette, and I am still too intimidated to prepare a mate myself.)

Most importantly, mate is shared. It is shared with everyone you are with. But it is also shared with others as a cordial way of being friendly. (I was on a hike and came across a couple drinking mate on a large boulder. I said hi in passing, and they said hi back and invited me to share their mate, as if it was a natural part of greeting another person.)

It is a group activity.

It is an event (“let’s go drink a mate”).

It is a part of every gathering.

It is taken (along with a thermos of hot water) when you travel, on road-trips, on hikes.

While I’ve never been into sharing drinks with people, the gesture of someone offering you a mate is so nice that I admit that I shared a lot of mates before the arrival of the coronavirus here.

Mate is usually drunk “amargo” (bitter) – just hot water and tea. But some people prefer “mate dulce”, with sugar added.

Before I arrived in Pagancillo, I had only tried mate amargo, but there with Marisel and Dario I experienced mate dulce for the first time.** (I prefer amargo but dulce is also nice.)

As we chatted, I learned that Marisel runs the tienda (convenience store) and Dario works at the National Park where I wanted to go the next day. (That was lucky because I wasn’t sure how I was going to be able to get to the park the next morning and he said I could go with him!)

The young woman I had seen when I got there was a visiting park guard renting the room next to mine. When she returned from collecting algarroba (carob) beans, we walked down to the river together, taking our shoes off and following the river all the way back to the main road – a hike she hadn’t done before either.

Like many women my age I have met on this trip, she has a daughter that is just starting college this year. She explained that she lived in La Rioja with her daughter but had been doing the park guard exchange here for about a month and had fallen in love with the town. Now that her daughter is in college, she was thinking of moving to Pagancillo, she loved it so much.

Eating dinner at a local restaurant (on the next block over – the town is just a few blocks wide in each direction), I met a Porteña couple – a couple from Buenos Aires. They invited me to sit with them, and we chatted for hours. They were really passionate about the movement to legalize safe abortions in Argentina (all abortions are illegal in Argentina), arguing that many people end up dying from illegal and unsafe abortions, while others end up requiring extensive assistance from the government to care for unplanned children. (It is one of the larger, more popular movements at the moment in Argentina, and I have met many people along my journeys – men and women alike – that are passionate about it.***)

The information I had found on the internet about how to visit the national park in the area was really not very clear, and my new Porteño friends explained to me that there were actually two different companies, at two different park entrances, that led tours into the park…making it all less clear to me.

When I arrived back home late that night and shared a mate with Dario and Marisel, I learned that the majority of the park guards lived there in Pagancillo, and I would be able to take a van with Dario the next morning to get to the park. I had gotten pretty used to just figuring thing out as I go, so I prepared my things to take the next morning and then fell asleep to the backdrop of small town silence.

I had waken up in a random small town that I had never heard of before arriving (Chumbicha), and now I was falling asleep in another cute, small town that I had never heard of before arriving (Pagancillo). In both places I found a peaceful, almost utopian way of life with incredibly friendly people. I decided that small town hopping was going to be my primary travel strategy from now on.

Footnotes:

*Mate photo credit: wikipedia

**No photo credit: I failed to get photos with Dario and Marisel.

***The topic surprisingly came up in many conversations where I never would have expected it to. For example, riding back to Bariloche with an older man who was a cell phone tower technician brought it up and explained that while he would never let his wife to have an abortion, he still thought it should be legal and should be an option for women.

In less than 24 hours I was so lucky to get a taste of this great little town and not just peek into the lives of some of the locals, but actually feel a part of it.

In less than 24 hours I was so lucky to get a taste of this great little town and not just peek into the lives of some of the locals, but actually feel a part of it.