My journey on “La Ruta 40” has been a unique adventure that I will never forget and that is impossible to describe in detail unless I write a book (which I might.) What really marked my journey, even more than the amazing landscapes, were the people I met along the way.

It was an unforgettable experience of connecting and sharing with so many different people, and just being overwhelmed by the generosity of people. In some ways, this has been the heart of my journey – where I’ve really had the opportunity to do what I came to do – connect with people and share experiences, getting a glimpse into the lives and hearts of people here.

In the next few posts, I’ll try to share some of those encounters (as well as the landscapes behind the conversations).

Part I – Salta

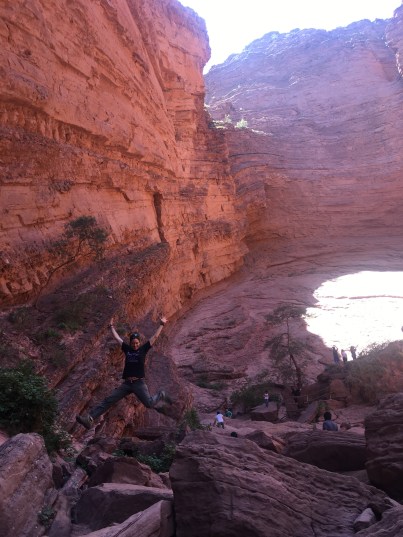

Salta is a city in northern Argentina, just south of Jujuy. In Spanish, “salta” means jump. So I did.

And in so doing, I met a French traveler, Thierry, and we became travel buddies for the day.

We explored the city parks together, tasted some ham and cheese empanadas, and people-watched, as the parks were full of people enjoying the beautiful weekend day.

In Salta, I stayed with Facundo, or “Facu” (a common name here). From the moment we met, we had some incredible conversations, so much so that we chatted into the night even though we were both running on very little sleep. But this is why I couchsurf – it’s a chance to meet someone from a different city, a different country, a different reality, and share experiences.

Facu is a super sharp guy around my age, studying biology because, he explained, that any job he got would require him to work a lot of hours and probably still not pay great, so he’d rather study something he really loves so that he can at least be doing something he’s passionate about. He’s a realist. He said I left him feeling more inspired and empowered that he could have a positive impact on the world. Which was incredibly flattering and in turn made me feel inspired!

In the grocery store line, I met the nicest woman. You know how the grocery lines can be pretty savagely competitive – everyone wants to be first in line and find the shortest line, especially when the wait is long. Well, this woman went out of her way to try to find the shortest line for me since I only had 2 items. (And I wasn’t even in a hurry, she was just being incredibly thoughtful.) We started chatting and it turns out that she’s an accountant that works in a government agency looking at the economic side of the “triple bottom line” (economics-environment-social impacts) for projects – coincidentally, my line of work and my passion!

On my way out of Salta, I met Valentina who is my age, and a lawyer from Buenos Aires. She had quit her job and before moving to the next one, was taking a vacation with her partner (who was from Paraguay and was traveling through South America). They had been to Patagonia together and invited me to join them exploring a beautiful part of “La Ruta 40” as they headed to Califate, a tiny town in the wine region.

They also spoke English so we ended up speaking a mix of English and Spanish, conversing the whole way and stopping to see a few of the most interesting spots – Garganta del Diablo and El Anfiteatro (which happened to be filled with tourists at this time of year*).

When I told Valentina about my Peace Corps work in Peru with water systems, she told me that she has been doing a volunteer project for eight years, working with a small community called Arbol Blanco in the province of Santiago de Estero. With an NGO from Buenos Aires, they work to empower the youth and help them take advantage of educational opportunities that could give them more professional options as they become adults.

We completely geeked out about sustainable community development work, really connecting with some of the similar experiences we’ve had. Similar to my experience working with Engineers Without Borders, she has witnessed the importance of being a long-term community partner and facilitator – focusing on cultural exchange and helping the community achieve its own stated goals, (rather than trying to do short-term projects based on funder priorities, which have a high failure rate). As we parted ways, I was excited to have met another kind and kindred spirit, (and also excited about the possibility of lending a hand if they needed any WASH (Water And Sanitation & Hygiene) expertise).

As if I hadn’t met enough wonderful people, I finally met Gabriela who went out of her way to drive me to meet up with my friends. A fellow lover of the night sky, she pointed out the observatory nearby and we made plans to go if we ever crossed paths again in the future. As we went our separate ways, I didn’t hear from her again, until one day, a month later when Argentina enforced the mandatory isolation measures, she messaged me to check in and offered me a place to stay if I should need it.

The beginnings of my journey along “La Ruta 40” were renewing my faith in the good of humanity and showing me the power of human connection and cultural exchange.** I was excited to see what lie ahead and only hoped that I hadn’t used up all my good luck.

Famous Footnotes

*This was during Carnaval season, which happens while school is out and is when the majority of people take vacations in Argentina.

**”Se que hay mucha mas gente buena que mala. Pasa que los malos hacen mas ruido.” – Dany Reimer

(“I’m certain there are more good people in this world than bad. The thing is that the bad ones make more noise.”) – Dany Reimer (Police officer in one of the toughest areas of Buenos Aires)

Maybe the beautiful bike rides through nature are what help me manage my stress and adapt to challenges, or maybe I’ve just gotten used to so many things always changing at the last minute or “going wrong”. Either way, I’m really hoping the patience, stress management, and adaptability that I’m learning to practice here can be translated to other situations… like long lines in the grocery story, rush hour traffic, bad customer service… and all those unexpected annoyances and challenges that life is sure to throw at me in the future.

Maybe the beautiful bike rides through nature are what help me manage my stress and adapt to challenges, or maybe I’ve just gotten used to so many things always changing at the last minute or “going wrong”. Either way, I’m really hoping the patience, stress management, and adaptability that I’m learning to practice here can be translated to other situations… like long lines in the grocery story, rush hour traffic, bad customer service… and all those unexpected annoyances and challenges that life is sure to throw at me in the future.

I think it was more exciting for me than them (I was a little underwhelmed by their reactions), but they had a great time and learned quickly about waves – how they surprise you and splash you in the face with salty water, and about sand – which doesn’t come out of your hair and swimsuit for a few days after rolling around in it like they did!

I think it was more exciting for me than them (I was a little underwhelmed by their reactions), but they had a great time and learned quickly about waves – how they surprise you and splash you in the face with salty water, and about sand – which doesn’t come out of your hair and swimsuit for a few days after rolling around in it like they did!